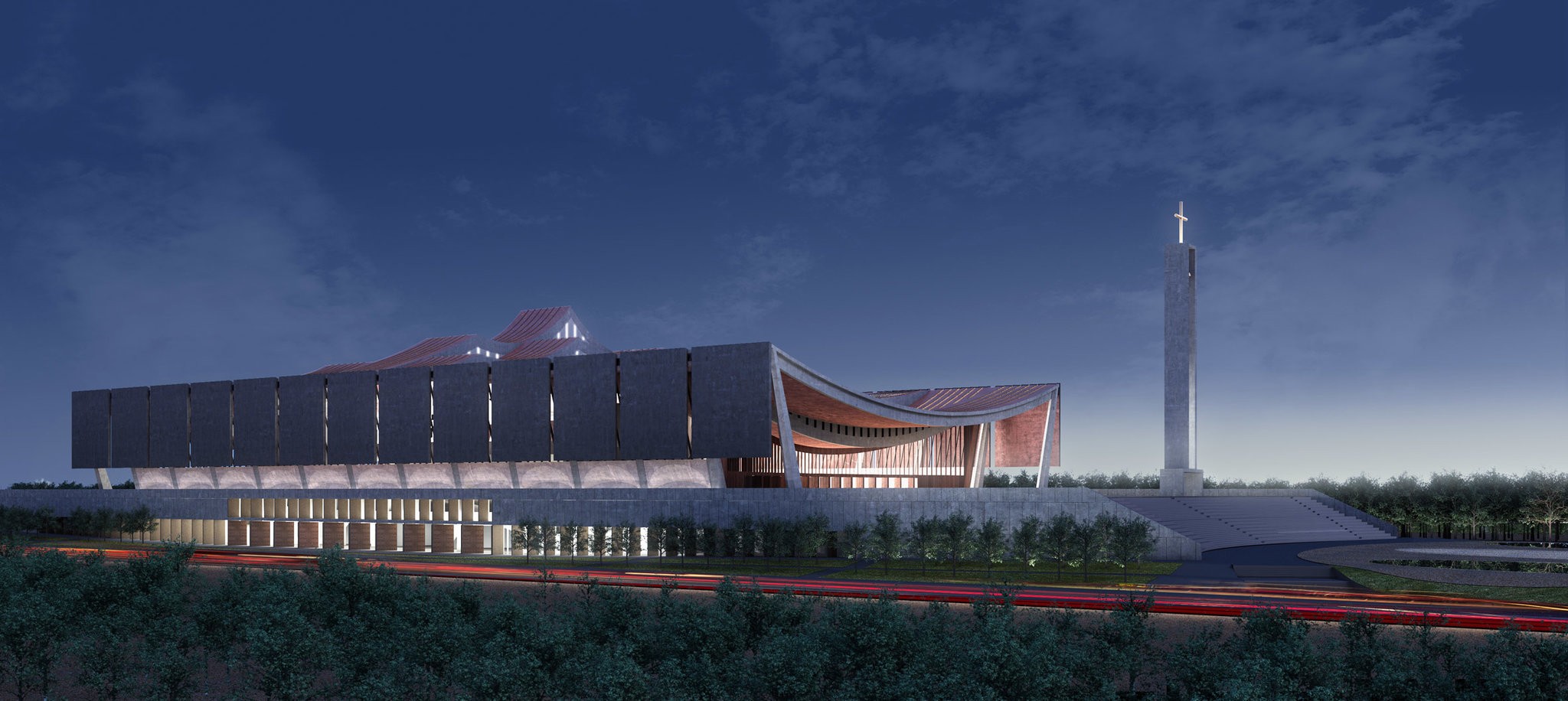

National Cathedral of Ghana, designed by David Adjaye

Last month, the president of Ghana, Nana Akufo-Addo, unveiled the design for a national cathedral that the government will build in Accra. This is a huge deal. It signals that the country is poised to consolidate the gains of decades of democracy. And the new interdenominational Christian cathedral will inspire ambitious civic architecture projects across the continent that harness the talents of Africa’s emerging artists.

Not everyone is cheering, though. Some West Africans have complained that the mixing of church and state is ill advised. They argue that it’s a worrisome case of official partisanship in a part of the world rived by religious conflicts. Others say the money for the project should have instead been invested in schools, hospitals and infrastructure — stuff that, according to them, Africa really needs. They are right to point to these endemic problems; but they are wrong to connect them with the cathedral.

The cathedral is the first major project in Africa by the Ghanaian-British architect David Adjaye, who was knighted last year for his services to his field. He is perhaps the most exciting architect in the world. His reputation is built on his stunning designs for Rivington Place in London, the Moscow School of Management Skolkovo, and, most spectacularly, the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture in Washington.

This Accra commission is not just a recognition by his homeland of Mr. Adjaye’s acclaim. It also signifies that Africa can build a major work by a leading architect at the top of his game. This is a remarkable thing: Ghana will get to brag about a globally recognized architectural landmark.

Mr. Adjaye has designed a fabulous church, with chapels, a baptistery and a 5,000-seat auditorium where state religious events will take place. But I’m thankful it’s more than that; it also includes an art gallery, a music school and a bible museum.

Also, there’s something worrisome about the idea that until every home in Africa gets a mosquito net, every village a school, it should not build concrete dreams and inspiring structures. This mind-set has strange old bedfellows in the refusal of colonial governments to build universities in West Africa in the early 1900s (because what the colonized needed was basic education) and the defunding of higher-education institutions in many parts of the continent beginning in the 1980s (because poor countries could not afford them).

To rise, Africa has to aim beyond basic needs. It must have infrastructure projects and superb schools that will also propel its growing economies. It must have also enduring and inspirational buildings and environments that unapologetically reflect its rich and complex histories, while also affirming the possibilities of a democratic and prosperous continent. The cathedral project is an emphatic example of necessary institutions, like public museums, that provide space for collective social, cultural and, yes, spiritual transactions.

Ghana has been heading in this direction since the 1990s, after years of military coups, dictatorships and economic distress. In 1992, the National Theater in Accra, designed largely by two Chinese architects and paid for by China, opened. Now, tourists and locals marvel at its elegant design and flock to its dance and theater programs. In 2008, the presidential palace was rebuilt. Inspired, like the cathedral, by Asante royal stools, it greatly changed how that part of Accra looks.

But these buildings were designed by foreign architects. This, too, has a history. During the age of exploration and the slave trade, Europeans built the massive forts and castles dotting the African coast, including the 17th-century Osu Castle, known as Fort Christianburg, which was the seat of Ghana’s government until a few years ago.

Source: Chika Okeke-Agulu